My Experience at La Nuit des Chercheur(e)s in Toulouse

In October 2024, I had the chance to take part in La Nuit des Chercheur(e)s (Researchers’ Night), an event hosted at the Cité de l’Espace in Toulouse, France. Every year, researchers step out of their labs and meet the public on an evening of discovery, activities, and conversations. For me, it was a great opportunity not just to share my work, but also to challenge myself as a science communicator in a new language and conditions.

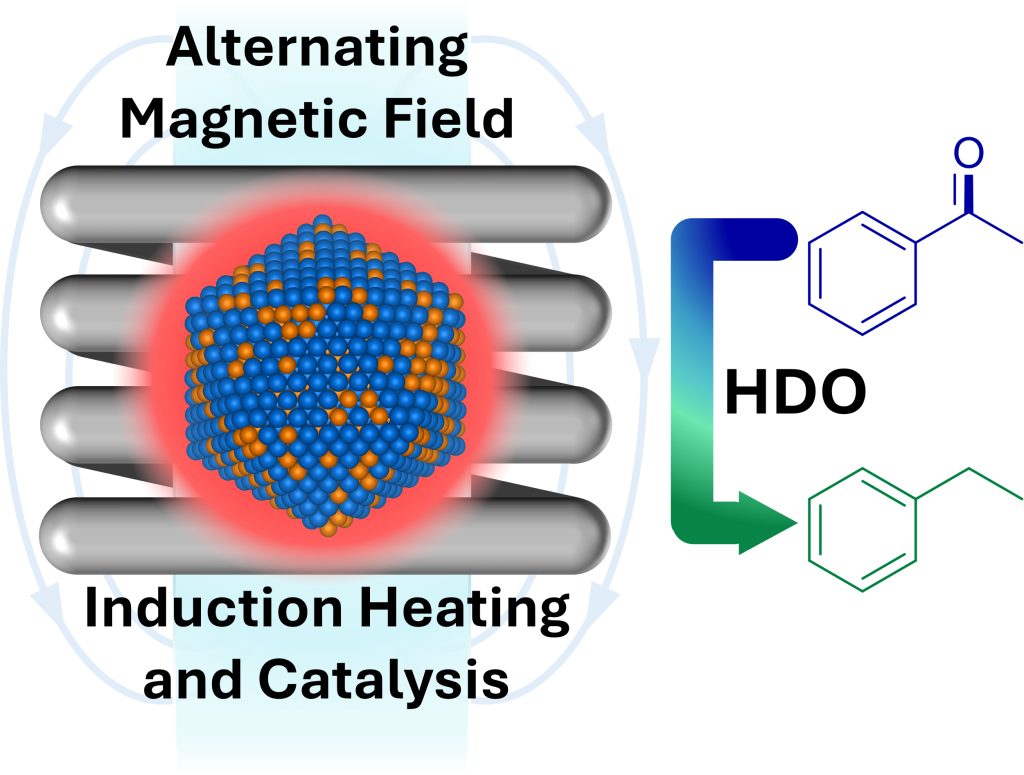

Together with my group of colleagues (Oscar Suarez-Riaño, Victor Varela-Izquierdo and Jaime Mazarío), we were part of Le Grand Labo, a big interactive space filled with stands and experiments. Our stand was called “Quoi? Des Nanoparticules?” (“What? Nanoparticles?”) from the research group I belong in France and led by my supervisor Lise-Marie Lacroix. Our goal was to show visitors how we use magnetic nanoparticles (NPs) for heating through magnetic induction, and how these same particles can act as both heating agents and catalysts at the same time.

Induction vs. Conventional heating: Going to the basics

One of the harder parts of preparing the stand was figuring out how to explain induction heating in a way that made sense to everyone, from kids to adults. On paper, it sounds like a very technical idea. But with the right analogy, people quickly got it. We compared it to cooking. Conventional heating is like boiling water on a stove: the burner heats the pot, and then the pot heats the water, a lot of energy is lost along the way. Magnetic induction, on the other hand, lets you create heat “directly” in the material.

When nanoparticles are placed under an alternating magnetic field, they rapidly generate lots of heat right where it is needed.1 What makes this even more interesting is when you combine it with catalysis. We can design nanoparticles that not only produce heat but also speed up chemical reactions.2 So instead of needing two separate systems: one to heat and another to catalyse, you get both functions in the same material. That means processes that are faster, more efficient, and potentially more interesting in terms of green chemistry.

Sharing science in French

Explaining this was not just about simplifying concepts, it was also about doing it in French. I’m used to presenting my work in English or sometimes in Spanish (my native language), but here the whole interaction was in a language I do not use frequently for science. At first it felt like an extra obstacle, but it quickly became one of the most rewarding parts of the night.

Every conversation pushed me to be creative. Sometimes I had to switch from technical words to metaphors or even use gestures and drawings when I couldn’t remember the right term. This constant back-and-forth made the discussions more dynamic, and honestly, more fun. By the end of the evening, I knew that the language challenge had helped me improve as a communicator overall. It reminded me that explaining science is not really about sounding perfect, but it is about connecting with people while being clear and concise.

A diverse audience with diverse questions

One of the things I enjoyed the most was the diversity of the audience: families with kids, teenagers in groups, older couples… Everyone came with their own curiosity, perspectives and questions. With children, I kept things very visual: magnets, models, colours, and simple images of nanoparticles. Teenagers often wanted to know about applications: Can this be used in medicine? Can this be used in everyday life? Adults tended to focus on practical aspects: efficiency, costs, and how this compares to what we already have as heating sources or catalytic materials.

We rapidly realised that instead of just “teaching,” we were having real conversations. The public didn’t just listen passively; they challenged us, asked smart questions, and made us think about our research from angles we do not always have totally in mind.

Why I would recommend it

I can definitely say this experience was a very nice way to begin my PhD. It brought together several things I really value: the chance to share what I do, the challenge of communicating in another language, and the joy of seeing people of all ages get excited about science. For any PhD student or early-career researcher, I would absolutely recommend events like this. We often spend most of our time inside the lab or writing papers that only specialists read, but the truth is that science should not end there. Sharing openly what we do not only helps people understand why research matters, it also gives us fresh motivation and perspective.

When I left the Cité de l’Espace that night (after midnight), I was exhausted. Speaking French nonstop for hours kind of burnt my brain, but I also felt satisfied. Inspired by the curiosity of the visitors, by the questions they asked, and by the reminder that science has the power to connect people of different ages, cultures, and languages.

References

- Mazarío, J.; Ghosh, S.; Varela‐Izquierdo, V.; Martínez‐Prieto, L. M.; Chaudret, B. Magnetic Nanoparticles and Radio Frequency Induction: From Specific Heating to Magnetically Induced Catalysis. ChemCatChem 2024, 17 (2), e202400683. ↩︎

- Quiroga-Suavita, F.; Varela-Izquierdo, V.; Hungria, T.; Alloyeau, D.; Ratel-Ramond, N.; Cayez, S.; Tilley, R. D.; Baquero, E. A.; Chaudret, B.; Lacroix, L.-M. Icosahedra CoPd Bimetallic Nanoparticles for Magnetically Induced Aromatic Ketone Hydrodeoxygenation. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37 (8), 2762-2771. ↩︎

Find out more about my research project here.

Categories

Latest posts

Stepping Into the Research World: Growing Through Three Conferences

My Journey Into Low-Dimensional Nanomaterials

Catching Atoms in Motion: First Beamtime Experience at ALBA Synchrotron